“We need, in every community, a group of angelic troublemakers.”

— Bayard Rustin

When we tell the story of the civil rights movement, we often hear the names Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, Malcolm X. But standing quietly behind so much of that progress—organizing, strategizing, making the dream march—was Bayard Rustin.

Black. Gay. Brilliant. Often erased.

Rustin was the architect of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, one of the largest and most effective political demonstrations in U.S. history. But because of his sexuality, even his closest allies asked him to stay out of the spotlight.

He didn’t stop.

Bayard Rustin’s life teaches us that power isn’t always loud. Sometimes it looks like steady, brilliant work. Sometimes it’s the hand that holds the plan, not the mic.

And yet—his radical vision was clear: no justice is real unless it’s for all of us.

A Life Between Movements

Born in 1912 in West Chester, Pennsylvania, Rustin was raised by his Quaker grandmother, whose values of nonviolence and equality shaped his worldview early on.

Rustin became involved with the Fellowship of Reconciliation and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in the 1940s, helping to pioneer the use of nonviolent direct action in the U.S. long before it became the mainstream civil rights playbook.

He was jailed as a conscientious objector during World War II. Arrested for being gay in 1953. Threatened. Blackmailed. Shunned. But he kept showing up.

It was Rustin who introduced Dr. King to the philosophy of Gandhi’s nonviolence. It was Rustin who planned the intricate logistics of the March on Washington. Buses. Food. Security. Permits. The hard, quiet labor of making change real.

“The proof that one truly believes is in action.”

— Bayard Rustin

Erasure and Exile

Despite his brilliance, Rustin was often pushed to the margins. Fellow activists feared that his sexual orientation would be used against the movement. Some even tried to force him out entirely.

But Rustin understood the stakes. He stayed anyway.

He knew that fighting for freedom meant fighting for every part of yourself, and for the freedom of others to be fully themselves.

His later work with the A. Philip Randolph Institute and his advocacy for labor rights, anti-nuclear activism, and global human rights reflected a deep commitment to intersectionality long before the word was popularized.

Legacy in Focus

It wasn’t until long after his death in 1987 that Rustin began to receive proper recognition. In 2013, President Barack Obama posthumously awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, acknowledging the debt history owes to his brilliance and integrity.

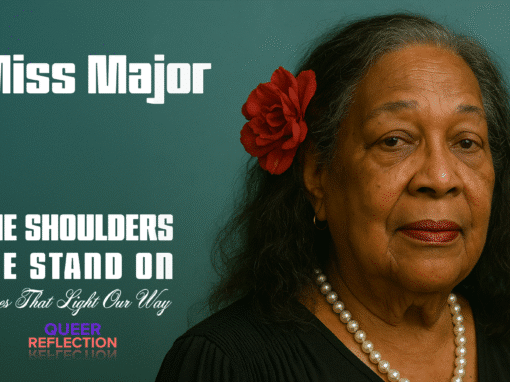

At Queer Reflection, we honor Bayard Rustin for reminding us that strategy is resistance. That quiet leadership is still leadership. And that justice means nothing if it’s not inclusive.

Learn More About Bayard Rustin:

- Bayard Rustin on Wikipedia

- Bayard Rustin Educational Resources (Learning for Justice)

- “Brother Outsider: The Life of Bayard Rustin” (Documentary)

- Presidential Medal of Freedom Citation

Reflection Prompt:

Where in your life are you called to be an angelic troublemaker?

How can your strategy become your act of resistance?